On July 17th, the FDA and Duke Margolis Center for Health Policy sponsored a workshop entitled “Improving the Implementation of Risk-Based Monitoring Approaches of Clinical Investigations”. The sessions featured 24 speakers representing the FDA, EMA, large pharma, CROs/AROs, clinical vendors, TransCelerate, MCC, SCRS, and SCDM.

This post focuses on the following points that were addressed during the workshop :

- Concept of Risk-Based Quality Management (RBQM)

- Risk-Based Monitoring (RBM)

- Risk-Based Monitoring Components

- Source data Verification and Review (SDV/SDR)

Please click on one the links above to go directly to the corresponding section of the post.

Often, the term Risk-Based Monitoring causes people to pivot directly to Source Data Verification. What is an acceptable level of SDV? If I do sampled or targeted SDV, does that mean I am running a risk-based trial? The experts speaking at the meeting consistently reinforced that the topic of SDV is a relatively small element of implementing risk-based approaches in clinical trials.

The first speaker was David Burrow, Director of the FDA’s Office of Scientific Investigations. David emphasized that clinical quality and regulatory compliance are not the same. He introduced the concept of Risk-Based Quality Management (RBQM) to ensure quality is consistently maintained in a clinical trial. RBQM encompasses Risk-Based Monitoring (RBM) – but includes much more.

He identified three common elements to RBQM:

- Risk Assessment (pre-study and ongoing)

- Well-designed and articulated protocol and investigational plan

- Risk-based monitoring plan

RBQM – From Box Checking to Critical Thinking

RBQM moves organizations from a “box-checking” QA mentality to a focus on risk identifying, monitoring and mitigation where critical thinking by experts drives quality. Speaker Steve Young, CEO of CluePoints, summarized the elements of RBQM as follows:

- Study design employing QbD principles: well thought out design, patient and site centricity, removal of non-core procedures

- Study planning and risk mitigation: critical processes and data identification, risk assessment and risk control

- Study execution employing targeted quality management: central monitoring, remote monitoring, and on-site monitoring

The Risk Assessment

Risk assessment and mitigation allows for the identification of higher risk areas that can be mitigated and lower risk areas that can be adapted and simplified.

Without a high-quality risk assessment, it’s not possible to execute a risk-based approach to a clinical trial. One presenter estimated that it takes a cross-functional team 20-80 hours to assess the risk for a specific protocol and develop appropriate mitigations. This also raises a point emphasized throughout the sessions: risks need to be study-specific.

David stated that a risk-based approach could not be layered on top of an improperly designed protocol (Although clearly several attendees felt they were being compelled to do this). Other speakers later clarified that there may be standard risks as well, but those are in addition to properly assessed study-specific risks.

Risk identification should focus on Critical to Quality (CtQ) parameters and not simply document the monitoring activities you are already doing. The TransCelerate Risk Assessment Categorization Tool (RACT), or a company-specific version, was mentioned as a source for risk assessment numerous times throughout the sessions.

The Protocol

The protocol establishes most expectations concerning the trial for the study team and the sites. It should identify CtQ parameters.

The Monitoring Plan

One of the speakers mentioned an old industry concept – the “Christmas Tree” protocol. This is a protocol that, like the Christmas tree you have in your attic, gets taken out periodically and added to – with new ornaments and decorations – but nothing ever gets taken away. He felt that monitoring plans are going in this direction – every time a new issue is uncovered, it’s added to the monitoring plan without a thoughtful re-examination of what is no longer needed, or not needed for a particular study.

Another speaker articulated the ideal approach to the monitoring plan with a quote from “The Little Prince”:

“Perfection is achieved, not when there is nothing more to add, but when there is nothing left to take away.”

Antoine de St-Exupéry

The monitoring plan should be reviewed and updated based on any updates to the risk assessment and mitigation plan, which themselves should be reviewed periodically. Monitoring activities need to be documented to demonstrate compliance with the plan.

The monitoring plan needs to be clear to CRAs (which number in the hundreds for large trials) and key elements also need to be explained to sites so they understand how they will be monitored. The FDA will often review the monitoring plan on request.

Finally, the monitoring plan is only one of a number of plans that should address risk including the medical monitoring plan, the safety management plan, etc.

Risk-Based Monitoring

Before beginning any discussion of RBM, it’s best to establish a common vocabulary, as it’s frequently found that not everyone has the same definitions for components of RBM. The facilitators provided the following definitions:

Risk-Based Monitoring: Monitoring that focuses sponsor resources and oversight on important and likely risks to investigation quality, including risks to human subject protection and data integrity, and on risks that may be less likely to occur, but that could have significant impact on the overall quality of the investigation.

Centralized Monitoring: Program of analytical evaluation carried out by sponsor personnel or representatives (e.g. clinical monitors, data management personnel, or statisticians) at a central location other than the site at which the clinical investigation is being conducted.

On-site Monitoring: In-person evaluation carried out by sponsor personnel or representatives at a clinical site at which the clinical investigation is being conducted.

Remote Monitoring: Monitoring of specific activities, as defined either within process documents or in the monitoring plan, performed by the monitor away from the site at which the clinical investigation is being conducted.

Adoption – and Barriers

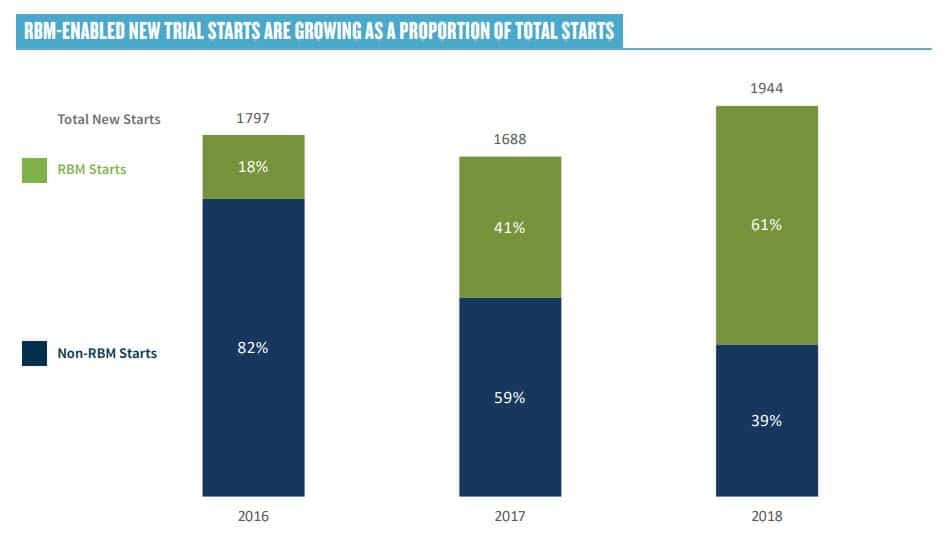

Throughout the day, there was considerable discussion on the adoption of RBM. In a recent survey published by ACRO, 64% of new trial starts are “RBM enabled.”

The consensus at the workshop was that large pharma and CRO have made extensive progress towards adoption RBM, but many smaller organizations are reluctant, often due to concerns coming from the QA function. Champions need to educate QA on the fact that RBM involves better understood risk, not more risk.

One attendee expressed an opinion that RBM should be considered a gift by QA, because it provides a mechanism for identifying preventative actions that would ordinarily not exist.

Several participants mentioned sponsors’ concerns that they would “miss something” in RBM studies. FDA’s advise was that they should be concerned about failing to detect systemic errors, not random errors – and that RBM will actually enhance your ability to detect systemic errors.

Tom Rolfe, Director of Risk-Based Monitoring at GSK, expanded on barriers to RBM implementation:

- Inconsistent acceptance of RBM approaches by regulatory authorities may negatively impact global product development programs

- Regional differences based on monitoring practices, GCP inspection experience and/or culture, etc.

- Industry concerns regarding RBM implementation of clinical investigations include:

- The quality of data

- Unknown audit findings by Inspectors and impact on registration

- Differences in clinical research organizations (CRO) RBM methodology and impact for sponsor oversight

- Accidental unblinding of sponsor

- Lack of clarity on how to implement RBM with differing study types.

- Complex trial designs

- Trials with a small sample size (e.g., oncology, biologics, early phase, umbrella & basket studies).

- Uncertainty on FDA expectations around Quality Tolerance Limits (QTLs)

- Data privacy regulations and evolving use of electronic medical records (EMR) for remote source document review

This discussion prompted requests for FDA to provide feedback or metrics on inspection findings in RBM studies as compared to non-RBM studies. FDA was not optimistic about this, saying that they have neither the sample sizes nor the resources to do this. This is also complicated by the fact that there is nothing close to a standard implementation of RBM. As David Burrows of FDA stated, “Just because someone might say that they have used risk-based monitoring… doesn’t necessarily mean that what they did is what we believe risk-based monitoring should be.”

Flawed Approaches, Poor Outcomes, Significant Potential Value

David Burrow of the FDA offered some insight into what not to do in implementing RBM. Specifically, he mentioned the following flawed approaches:

- Switching to centralized monitoring without implementing a plan to guide what is being looked for, why and when. Shifting to 100% centralized monitoring is not risk-based monitoring.

- Simple random sampling approaches without “intent” and a risk-based plan

- 100% SDV with no focus on CTQ – this is just looking for transcription errors, not elements that are critical to quality.

He referred to these as failures in the worst cases, and lessons learned in better cases.

David also addressed the value that the FDA sees in RBM and encouraged the industry not to let fear act as a “bungee cord of resistance” in making progress.

The Value of Risk-Based Monitoring:

In some instances where we’ve seen true risk-based monitoring implemented, we have seen a great correlation between the issues that were identified in the risk-based monitoring system and the issues we see in the application review on the back end. So anecdotally, I think that works really well.

David Burrow, FDA

Sponsor RBM Experience – Positive Perceptions

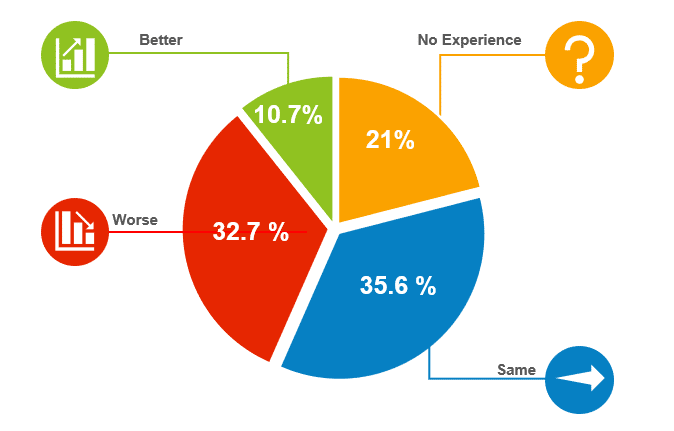

Justin Stark of Novartis, presenting on the behalf of Transcelerate, shared the results of a member survey that included eight measures: audit findings, SAE reporting, significant protocol deviations, overall monitoring costs, on-site visit interval, issues open to close, eCRF entry, and query open to close.

For all eight measures, at least 50% of sponsors reported better outcomes (and at least 70% reported the same or better). For example, for audit findings, 62% reported better outcomes, 30% were largely unchanged, and 8% were worse.

Site RBM Experience – Less Positive Perceptions

Michele Cameron, Director of Clinical Research for Clearwater Cardiovascular, spoke on behalf of the Society for Clinical Research Sites (SCRS) and discussed site experience with RBM. She presented the results of a 2016 survey of 309 sites on their experience with RBM, which was disappointingly poor.

The survey measured a total of 12 factors on how RBM has impacted the site, with a significant number of sites reporting increases in regulatory obligations, workload, resource needs and cost. A significant number also reported a degradation in their relationship with the associated sponsor or CRO and a decrease in the number of patients they were able to see.

She attributed problems to the CRA not being able to provide clarification on the monitoring plan, work being passed on to site that were not their responsibility.

She felt that there is a need to account for site diversity (size, structure, operation, and experience). Sites also need a clear RBM guideline from the inception, and preferably input into the plan. They need knowledgeable contacts that can answer sites quickly and would benefit from the monitor having a trigger for collaborative phone calls instead of constant, repetitive e-queries. Finally, she recommends less frequent, more substantial phone visits.

Risk-Based Monitoring Components

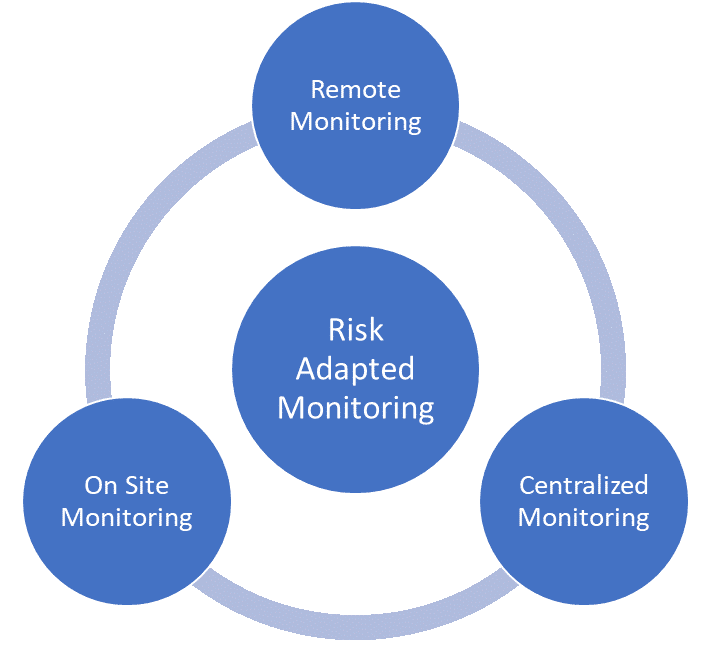

The following definitions were provided for risk-based monitoring components:

Centralized Monitoring: Program of analytical evaluation carried out by sponsor personnel or representatives (e.g. clinical monitors, data management personnel, or statisticians) at a central location other than the site at which the clinical investigation is being conducted.

On-site Monitoring: In-person evaluation carried out by sponsor personnel or representatives at a clinical site at which the clinical investigation is being conducted.

Remote Monitoring: Monitoring of specific activities, as defined either within process documents or in the monitoring plan, performed by the monitor away from the site at which the clinical investigation is being conducted

All three types of monitoring can be risk-based. An assessment of the protocol and overall risk assessment should be used to determine which components should be used and how to implement them.

Centralized Monitoring

The goals of centralized monitoring can include:

- Identification of:

- Missing or inconsistent data

- Data outliers

- Unexpected lack of variability

- Protocol deviations

- Systematic errors

- Data integrity issues

- Analysis of:

- Data trends (e.g. range, consistency, variability of data) within and across sites

- Site characteristics and performance metrics

- Selection of sites and/or processes for targeted on-site monitoring

Stephanie Clark, Director Risk Management – Central Monitoring at Janssen, outlined her organization’s approach to centralized monitoring:

- Standard Key Risk Indicators (KRIs): Dashboard with standard operational and safety KRIs to indicate potential risks in countries/sites. Applicable across studies

- Study-Specific Reports (SSRs): Visualizations based on unique, study-specific Critical to Quality (CtQ) factors to identify potential risks in study/countries/sites

- Central Statistical Surveillance (CSS): Statistical analysis of entire trial data set to identify signs of intentional/unintentional noncompliance. Identifies sites that need further focused monitoring

Janssen has tried to “democratize” data insights – so everyone from CRAs to study physicians to clinical operations leaders have access to this data. Users also receive role-specific training on how to leverage these insights.

There were several interesting examples of signals monitored using centralized monitoring. It was emphasized that these signals are not inherently problems, but instead require investigation.

- IQVIA – mechanisms for fraud detection, including potential duplicate subjects and visits, digit preference and roundoff, and patient or lab visits on weekends or holidays.

- Janssen – examination of oncology trial subjects who had reported no adverse events – especially when linked to certain sites.

- Janssen – detection that biomarker samples were not taken for two consecutive months at a specific site. The site was retrained, and the issue did not reoccur.

- MCC – significant expedited ordering of lab kits, often indicating that new, untrained study personnel had joined the study. In this case, this was a signal that would come from working with a partner, and that partner would need a channel to report their concerns.

Many times, data can’t really be analyzed until enrollment is well underway or complete as analysis requires a meaningful data set to be valid. It often takes experts to pull out true findings from noise, and to explain findings to study teams in such a way that they are meaningful and actionable. Control over who is looking at the data and how is often needed to prevent accidental unblinding.

Remote Monitoring

Participants were seeing more tools that allowed remote monitoring and source data verification, including wearables, electronic health records, ePRO, and eConsent. For some of these technologies, there is a risk tradeoff, as tools such as ePRO and wearables are less tightly controlled than EDC.

One participant from a medical device company described her organization’s approach to remote monitoring as very similar to onsite monitoring, just without the physical presence:

- Confirmation letters, visit reports and follow-up letters generated in the same manner as for an onsite visit

- Study coordinator sets aside time for the visit

- Investigator confirms availability

On-Site Monitoring

Of course, there are also risk adaptations that can occur within an on-site monitoring framework. At the most basic level, the expected frequency of site visits must be established, and the triggers for changing the visit interval based on the perceived risk identified. This is a very significant issue for CRO-run trials as cost models depend on the expected number of visits. Sponsor and CRO should discuss how costs will be handled if more frequent visits are needed.

Stephanie Clark of Janssen mentioned that her organization can take some data review activity and move it to in-house roles who can look at data early and in an ongoing fashion. This means there is sometimes an opportunity to do fewer on-site visits. Visits can then be spent doing activities that uniquely require CRAs to be on site.

Source Data Verification and Review

A significant portion of the conference was devoted to SDV and SDR.

Source Data Verification (SDV): the process by which data within the CRF (or other data collection system) are compared to the original source of information, to confirm that the data was transcribed accurately.

Source Data Review (SDR): the review of the source documentation to check on quality, compliance, staff involvement, and other areas that aren’t associated with a CRF data field.

Almost universally, both presenters and participants were skeptical about the value of SDV and generally considered SDR to be much more valuable. Some opinions included:

- 100% SDV adds risk. This is because it is done at the expense of important monitoring activities such as training, and because it shifts the focus away from risks to the most critical data elements and processes.

- SDV is a proxy to see if something is wrong with the site. That is, sloppiness in data entry could indicate more extensive problems.

- SDV is mainly justified if critical endpoints exist where transcription errors could have a high impact.

Research supports the conclusion that 100% SDV plays in overall quality. For example, a survey by TransCelerate indicated that:

Despite variability in the way companies manage their data review activities, all companies were similar in the low rate of SDV-generated queries. The average percentage of SDV queries generated was 7.8% of the total number of queries generated.

[Source: POSITION PAPER: RISK-BASED MONITORING METHODOLOGY]

A TransCelerate survey of 17 members provides insight into sponsors’ view towards SDV use by their CROs. 94% indicated that 100% SDV of all data points is not required of their CRO partners. 6% (1 company) does require it. In terms of providing guidance to CROs:

- 53% provide guidance on SDV levels, but allow flexibility

- 29% do not give specific guidance on SDV levels

- 12% give specific SDV levels, no flexibility

- 6% do not use CROs

Nicole Stansbury, Vice President, Central Monitoring Services for Syneos Health, described a methodology that included:

- Reduced SDR/SDV, based on the use of a risk assessment – identifying SDV to be verified based on visits, subject, or data points

- Targeted SDR/SDV driven by central monitoring findings

Sharon Love of MRC Clinical Trial Unit at UCL presented research on measuring RBM and SDV. Conclusions included that risk-adapted monitoring was not inferior to extensive on-site monitoring, and 100% SDV was little different to SDV of key scientific and regulatory variables.

Throughout the session, it was emphasized that 100% SDV has been implemented by a conservative industry, not dictated by the regulators.

FDA guidelines explicitly refer to a representative number of subject records, not all subject records. ICH GCP states that a “Statistically controlled sampling may be an acceptable method for selecting the data to be verified.”

David Burrow, Director of the FDA’s Office of Scientific Investigations, summed up the attitude of the FDA to SDV:

We’re not saying not to do any source data verification any more, but it should be done with intent, when it’s indicated for the right purpose.

David Burrow